Review by Ayodeji Kumuyi

General Overview

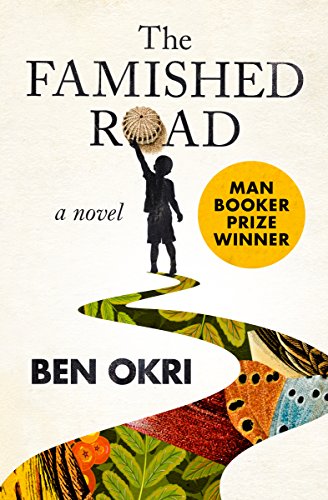

Winner of the 1991 Booker Prize, Ben Okri’s book, “The Famished Road”, follows young Azaro (full name Lazarus), an “Abiku”, or “spirit-child”, who decided to stay after being born, thus reneging on his pact with his fellow spirit-children, whose attempts to lure him back form an interesting backdrop to the story, and his poor family.

The book is set in the tense years leading up to Independence, in a small poor town. There isn’t any inequality in the town: Everyone is dirt poor. With the coming of the nation’s economic and political self-determination, things began to change. The political turmoil, the fighting by the two major parties, aptly called the Party of the Rich and the Party of the Poor (even though there is little difference in their approach beyond rhetorical bluster), is mirrored in the industrialization and electrification of the town, as we see the seeds for the type of political canvassing we have today and the unequal distribution of resources take root.

Okri brings the full depth of the African experience to life in this book. Our animism, often dismissed as primitive, is shown to be filled with life, even if not with joy. The blurred lines of political thuggery, the mixture of traditional religion and the religions brought by colonialism, the perils of repression, the fickle nature of the public, there’s a lot to unpack in this book, and a lot to learn.

But first, the characters:

Azaro’s parents are an interesting bunch. His father is an herbalist’s son (not just any herbalist, as reading the book will show), an “alabaru” (load-carrier), and a quite formidable boxer who, in his way, is a pastiche of Muhammad Ali, especially near the end of the book, where he begins to devour books and talk about politics. He reminds me of one okada rider I saw this week, whose tone and depth of voice, when he started talking to his friends, sounded very much like the legendary anime villains, particularly Madara Uchiha. “In another life”, I thought, “this man would be an esteemed voice actor”. And so it is with Azaro’s father. With him, one wants to tweak a few factors and see how his life would rapidly diverge from what we are shown. Even Azaro gets it. At a point in the book, the young boy sees two people who look uncannily like his father and mother coming out of a shop. At first, he doesn’t see any resemblance, but when they pass by him, it hits him and he refers to them as the “successful shadows” of his parents. The man is even in the French suit his father likes so much.

In the early parts of the book, his mother is the center of Azaro’s life. He stays in the world of man, after 5 cycles of coming and going, because of this woman. He bursts into tears when she confesses that she wants to die. His supreme goal is to make her happy. It is hinted that she was one of the most beautiful young women in the village they both grew up in. Their names are never mentioned. She becomes a hawker, then a stall owner, and then a hawker again after some good old-fashioned agberos destroy her stall because she refuses to vote for the party that pays their bills. When she is unlocked, she is quite fierce.

Their dynamic is quite peculiar. They have sex just once, he beats her twice and she apologizes for vexing him the first time, she practically saves his life not one time, he forbids her from working their frenemy’s place because he fears she will become a prostitute, he eats like a black hole, and she goes hungry many times in the book. He talks many times about joining the military and throws a big party that results in the family falling into debt twice. Without her, the family would go into ruin.

There are only four characters mentioned by name in this book. Azaro is one. The second is Madam Koto, a businesswoman, lowkey-witch, and pimp. In a way, these three words are an unfair mischaracterization, as she is much more than that. Her shop is the melting point where the world of spirits, ghosts, and the surreal come to meet with the world of roads and humans, and is where a lot of the spiritual action plays out or is started. Her shop is also a political melting point, as she is on good terms with many of the thugs of the rich party, and she benefits from it, becoming the first person in the entire village to have both electricity and a car. Madam Koto also develops something like a pregnancy towards the end of the book, one that Azaro looks into, and sees brimming with triplets who have no intention of being born.

There’s something though, that differentiates the thugs of Madam Koto’s day from the thugs of our present day. Her thugs bring wealth and progress to her shop, but in the present day, our political thugs bring almost exactly the opposite, since they drive away other customers who do not want to be involved in political matters. Koto’s thugs also throw a large banquet near the end of the book, and it’s unlikely thugs get access to that kind of money.

It could be that pre-independence thugs were paid more than post-independence thugs, even though they are no less crucial. Or it could be that Okri is implying that politicians and thugs are no different, intentionally blurring the lines between foot soldiers and higher-ups. It could be my hindsight bias talking, but two incidences (three, but the first two are similar enough to be grouped as one) lend some credence to my opinions. The first is the spoilt milk incidence, which I will not speak of because it contains the most illuminating dialogue on political campaigns in the book, and the second is the massive fight between low-level thugs of both parties. Okri speaks of them as not knowing which party they belonged to, just engaging in wanton violence. The switching and vagueness of sides hint at how frequently politicians then and now changed parties.

The third named character is Ade, the son of a herbalist and a fellow abiku. Ade and Azaro start out by fighting and grow to form an unbreakable friendship. Ade is Azaro’s partner-in-crime, and they go on many adventures together, though not the fun kind. Ade’s relationship with Azaro, though, is best understood as a conflict of opposites. Ade is an abiku who wants to return to his land of spirits, his idyllic land of his friends, and Azaro is the one who doesn’t want to return at all, who fights with all his might and doesn’t relent (except this one time) in his quest to stay alive.

The fourth is the beautiful, blind-in-one-eye, leader of the beggars, Helen. She follows Ade’s father around like a devoted puppy and the seeds of a relationship with Azaro are sown, but since the book doesn’t follow them around their lives, we never get to see what that is like.

There are also a number of unnamed but important characters, like the blind old man who also doubles as an accordionist and can see whenever he wants, the landlord who hikes rent constantly because of Azaro’s family’s political affiliations, and who shows up to collect debts or be a social climber within the political ranks of the Party of the Rich. There’s the photographer and rat-killer extraordinaire, who seems to capture time in his camera and due to his images, becomes a target for political repression and is the kind of person, that, were he in our day, would become rich and famous just by being “canceled”.

These unnamed characters exist not only in the human world but also in the spirit world. There are the monolingual rats who understand the speech of humans but cannot speak back to them, the three, four, and five-headed spirits sent to retrieve Azaro, the absurdly tall, shapeshifting spiritual kidnappers, the lizards, and the two-legged dog.

All these characters and their dialogues/encounters with Azaro paint a full picture of life, viewed with an expanded eye. In addition to that, the stories told to Azaro by his mother and father are used by Okri to depict just how rich our African experiences and our stories are, but he also used them to illustrate deeper truths about society and our relationship with our history and culture.

Placing The Famished Road within a larger context

While reading The Famished Road, I was struck by its thematic similarities to a book I consider one of the greatest works of fiction to be written, Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude. On the face of it, there’s an argument to be made that the only common ground between both books is the fact that the countries where the authors came from were former colonies. Garcia’s book is pre-colonial (although it ends in the colonial era), Okri’s is pre-Independence.

Looking deeper, though, that argument isn’t functional at all. Both straddle the line between reality and fiction, use their stories and experiences to illustrate deeper truths about their societies, and use what we might call “magic” as a literary device.

One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez belongs to a genre called “magical realism”, and I think Okri’s book should be placed within that larger context as well. Okri’s work is also a large contribution to the African literary canon because not that many books exist with such a wonderful, magical interplay between reality and magic. Things are not always what they seem, so Okri and Marquez tell us. One such book from an African that can be categorized under the magical realism canon is K. Sello Duiker’s “The Hidden Star”. I had the pleasure of reading it right in secondary school and I would recommend it to anyone looking to understand that genre in an African context.

Conclusion

I actually came upon this book by chance. I had read most or all of the designated books of the month, and I had completely forgotten about the book when I finished a book I had been struggling to read since the 19th of January. I had read the book before, but as with many books that shape attitudes, I forgot most of what was written, and I decided to revisit it at the start of the year. The book may not have been enjoyable, but it was very important to how I thought about statecraft, large-scale, high expertise-intensive projects, and the experts’ attitude to common wisdom. I only remembered The Famished Road because there was nothing else I was enthusiastic about reading.

I rarely read fiction, but I enjoyed this book immensely. It was enjoyable and fun to read, and it also provided a wealth of experience and wisdom about the human condition. I’ll definitely give it a 4/5 stars and I recommend this to anyone in this group who hasn’t read it before.